Reflections on our journey between 2018-2020

IT for Change | March 2020

Introduction

The Prakriye field centre of IT for Change has been engaged in deploying the creative potential of information and communication technologies in furthering socio-political empowerment of marginalized rural women and adolescent girls, and promoting gender-responsive local governance, since its inception in 2005. In its efforts to evolve a radically new development praxis that brings power to the peripheries, the centre has consistently engaged with rural women’s collectives (sanghas), adolescent girls, male community leaders, local government institutions and community-based organizations in over 60 villages of Hunsur and HD Kote block, Mysuru district. For a long time, the thrust of our strategies was on strengthening women’s access to public information and entitlements, amplifying their political voice, and opening up new opportunities for their public-political participation. Though we pursued a participatory community media strategy to tackle head on many issues of gender-based discrimination and social marginalization, we did not have a programmatic track that explicitly focused on addressing the ‘last bastion’ of patriarchy: gender-based violence

With support from Edelgive Foundation, we initiated the Namma Maathu, Namma Jaaga programme with the vision of building a supportive community ecosystem for prevention and redress of all forms of gender-based violence against women and girls in our operational areas. We began work in March 2018 across 25 villages of HD Kote block with the intention of gradually scaling up our intervention to Hunsur block as well, focusing on the following specific objectives:

- To make available locally accessible, women-centric systems of psycho-social support and access to redress and justice for women/ girl victims of gender-based violence.

- To ensure that frontline workers of the government system – anganwadi workers from Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) system and Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) from health system, who often interact with poor, rural women – are equipped to provide informed and empathetic guidance in instances of gender-based violence against women and girls.

- To create a dedicated space for nurturing local solidarity among women and building a local support network for them.

- To ensure that boys and men are part of the social transformation towards gender equality.

- To make women’s right to bodily integrity, well being and freedom from violence a society-wide imperative.

- To build a local public sphere, which makes room for women’s articulations, feminist viewpoints and progressive ideas on gender justice.

- To create a local ecosystem that disincentivizes public and private violence against women.

This report summarizes reflections about Phase 1 of the Namma Maathu, Namma Jaaga programme (March 2018-February 2020), capturing the highlights of our efforts to build a climate of zero-tolerance for gender-based violence at the grassroots. We have organized our reflections as a discussion on progress towards the three main outcomes envisaged at the start of the intervention.

Progress towards outcomes

Outcome 1: A multipoint support system that provides counseling and psycho-social assistance for women/girl victims of violence set up in 25 villages of HD Kote block

At the village level, women or girl victims of gender-based violence find it extremely difficult to access a first point of support. Family members are often judgmental or dismissive, traditional community leaders and panchayats tend to uphold patriarchal norms if called upon to mediate, and institutional mechanisms of support such as the Santwana helpline are often not within easy access. Therefore, as part of the Namma Maathu, Naama Jaaga programme, we were keen to set up safe spaces at the village level (Namma Jaaga gender help desks) womanned by a cadre of para-counselors recruited from the community and trained by the Prakriye team in feminist counseling methods.

Since anganwadi workers are officially mandated by the government to provide crisis support for gender-based violence at the village level, we felt that on-boarding anganwadi workers as para-counselors, and using a part of the anganwadi space at the village level for the gender help desks, would be a good strategy for sustainability. We utilized our pre-existing rapport and institutional relationship with the Department of Women and Child Development, Government of Karnataka to obtain permission for training anganwadi workers and utilizing anganwadi spaces for our intervention. Though initially we were planning to recruit and train three para-counselors per village, we made slight alterations to the design after assessing factors on the ground, such as the relative size of the village and extent of the time burden being placed on women community leaders.

51 women – including 34 anganwadi workers, 2 ASHAs, 12 active women from collectives and the 3 infomediaries associated with our pre-existing cluster information centres in HD Kote block – were on-boarded and trained as para-counselors. In partnership with Samvada, a Bengaluru-based not-for-profit organization with expertise in implementing short courses on feminist counseling, we designed context-appropriate para-counseling training modules, focusing on hands-on application of women-centric counseling principles: sensitivity, critical recognition of patriarchal and intersectional operations of gendered power relations, non-judgmental attitude, and respecting victims’ decisions to determine the pace of intervention.

With the anganwadi workers and infomediaries, we conducted the para-counseling training modules through three intensive residential workshops of three days each. With ASHAs and women leaders of sanghas who had signed on to be para-counselors, we carried out trainings at the village level.

Anganwadi workers found the training sessions on feminist counselling principles eye-opening, providing them with a transformative lens to analyze cases of violence.

After an initial round of trainings were completed with the para-counselors, we encouraged them to undertake household level visits in their communities in order to discreetly identify women and girls in need of crisis support for gender-based violence. Simultaneously, in order to prevent stigmatization of women from the community who visit gender help desks, we furnished these spaces with recreational board games, to facilitate the establishment of relationships that could potentially flower into peer support groups at the local level. We also modified traditional games such as ‘Snakes and Ladders’ to convey critical ideas about the obstacles that women and girls face from household level patriarchies and reinforce progressive narratives of women’s rights and gender equality.

The location of the gender help desks in anganwadi centres proved conducive to these social interactions and recreational activities as young mothers, pregnant women and adolescent girls approach the anganwadi for accessing many health and nutrition services. Our efforts helped even those women who are not associated with any sangha. Young women who had recently moved/migrated into the village after marriage found new friends and connections through these centres.

After an initial icebreaker through household visits and socialization at the gender help desk, the flood gates seemed to have opened. The 37 gender help desks set up in the 25 villages in our area of operation, received over 991 requests of help/crisis support from women and girls facing violence. We put in place a Management Information System (MIS) to track the nature of cases and to plan an intervention. We were keen to put in place a case documentation system that goes beyond the simplistic categories of “physical”, “sexual” and “psychological” abuse, addressing cases in their full complexity. Our documentation has thus been time-intensive because of an emphasis on qualitative aspects of cases. A broad overview of the types of cases that emerged is provided in the table below.

| Nature of the problem | Number of cases reported | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Husband refuses to provide financial support or neglects the household | 84 |

| 2 | Husband is addicted to alcohol and is physically violent when drunk | 99 |

| 3 | Other members in the marital home are physically or verbally abusive | 33 |

| 4 | In-laws are harassing for dowry | 32 |

| 5 | Husband suspects the wife and mentally tortures her | 74 |

| 6 | Husband is engaged in extramarital affairs | 38 |

| 7 | Cases of physical violence, mental cruelty or neglect that were referred to Santwana as victims wished to pursue legal remedies | 27 |

| 8 | Cases where victims withdrew from the legal process midway because of the logistical inconveniences involved | 2 |

| 9 | Other categories (mainly humiliation or intimidation by husband, preventing wife from undertaking wage labor, or violence against adolescent girls) | 602 |

| Total number of cases | 991 |

As this table demonstrates, very few victims exercise the option of pursuing legal remedies. The majority are content with psycho-social support and mediation of the issue at the community and/or family level in a manner that is empathetic to them.

The reluctance to pursue legal mechanisms is not surprising given the trajectories of the few who tried to access justice through that route. Police are often reluctant to file a First Information Report (FIR) and, instead, advise reconciliation between husband and wife. Even when an FIR is filed, obtaining hospital reports to support charges of physical violence and producing witnesses from the village to strengthen the victim’s case, becomes a further roadblock. The rare cases where the court delivers a verdict in the victim’s favor are often followed by caste leaders and informal community panchayats censuring or penalizing the victim for breaking village-level norms.

The facilitation of family and community-level mediation are often hindered by regressive gender norms. Family elders and community leaders believe that physical violence within marriage is commonplace and intervention is required only in case of grievous injury. There is also a tendency to dismiss abuse by men while in a state of intoxication. Comments like, “he couldn’t control himself”, “the woman should not have angered her husband when he was drunk” are commonplace. When a woman decides to do something about the violence, she is expected to toe the community norms that lay down how she should go about this so as to preserve the honor of the family and the village. Filing a police report usually results in the community’s refusal to support her if there is a recurrence of violence. It is expected that a woman should first go to her caste leader and then to village level meetings of caste/clan leaders (ooru koota). Needless to say, these forums are often hostile to the complainant and end up endorsing various forms of victim blaming.

Our experiences with setting up and rolling out the para-counseling system have underscored the importance of working on cultural transformation, questioning regressive gender norms and promoting progressive imaginaries of women’s rights and gender equality at the village level. As feminists have long acknowledged, structural change is not achievable overnight and requires sustained engagement at the grassroots. We do, however, have instances of slow but promising transformation, led by our para-counselors and infomediaries. One such experience is shared below.

We would like to highlight here that some of the para-counselors and infomediaries themselves have been able to further their journeys of empowerment because of the project. For instance, Sneha (name changed) is an anganwadi worker who herself was married off as a child. During initial interactions with her, we realized that she had internalized a number of mainstream ideas of male entitlement and privilege as well as the inevitabiility of male domination in family and public settings. She also had difficulties in seeing through narratives of victim blaming. But attending the training sessions, we noticed that there was a major change in her views about women’s place in the family and society. She gradually started to voice critical perspectives on the double standards of a patriarchal society and expressed her desire to work towards breaking down regressive social norms and prejudices that impede women’s lives.

When we designed the programme, we were cognizant that gender-based violence could not be effectively countered without addressing women’s overall socio-economic vulnerability. Hence, the facilitation of access to welfare entitlements for women from marginal social locations through our information centres has been a critical element of our strategy.

Between March 2018 to February 2020, our three cluster information centres in HD Kote block processed a variety of entitlement claims. These included applications for land title documents, income and caste certificates, Aadhaar and Kisan cards, insurance schemes, housing schemes, sanitation schemes, old age pension, widow pension, disability pension, pension for single women, loan for sanghas, scholarships, agriculture schemes, and household level LPG connections through PM Ujwala Yojana.

Information centres are the nodes of a local information and knowledge system owned and controlled by women.

The information centres have also engaged in a range of public information outreach efforts, in partnership with critical institutional stakeholders. For example, in partnership with the government’s Santhwana helpline on gender-based violence, community level sessions to build awareness among women and girls about the rights available to them under the Domestic Violence Act were organized. Skills trainings in tailoring and short courses in computer literacy were initiated in partnership with local institutions. Community meetings to facilitate access to bank credit through self-help group loan schemes of the National Rural Livelihood Mission were convened.

Outcome 2: Locally-grounded ideas of gender justice and women’s equality and dignity take root

Innovative digital media-supported learning dialogues with sangha women, adolescent girls and adolescent boys, and networking with influential male leaders were the main strategies that the Namma Maathu, Namma Jaaga programme deployed in order to promote progressive discourses of gender justice, women’s equality and dignity in the local public sphere.

Namma Maathu: Learning dialogues with sangha women

Sangha women have championed the higher education dreams of their daughters and contributed to furthering grassroots conversations on girls’ right to self-determine their life course.

Over the two years of this project, we convened monthly learning dialogues with sangha women, utilizing innovative digital media-based curriculum to unpack prevailing gender norms, roles and stereotypes and catalyzing critical thinking on patriarchy among the participants. Because of the lack of spaces for empowerment education and the reduction of sangha meetings to weekly gatherings that discussed savings and credit, these monthly dialogues (called Namma Maathu forums) generated great interest among local women’s collectives. We were able to cover over 1,250 sangha women through these forums, a target that far exceeded initial expectations.

In these forums, infomediaries and trainers from Prakriye who played the role of resource persons, used video resources to generate discussions on a number of issues: unequal division of chores in the household, the curtailment of girls’ education, the failure of panchayats to acknowledge public safety as an important local governance priority, and the linkages between household indebtedness and cultures of violence.

Conversations in the Namma Maathu forums have also inspired the creation of new curricular material. For example, the film Magale Hejje Irali Mundhe (Daughter, step forward) was shot after many sangha women shared their anxieties and concerns about supporting their daughters’ quest for higher education. This film shares the stories of women from the project area who braved family and societal opposition to permit their daughters to move outside the village and obtain college degrees. Screening this has been inspirational and helpful for many women participants in the Namma Maathu forums.

Another innovative learning tool that we deployed was a gender score card that helped women understand the operations of gendered power in the household, as well as the dissonance between women’s contribution to the household and their decision-making powers.

There are many stories on the ground about how the Namma Maathu forums enabled shifts in women’s awareness and ability to claim their rightful entitlements. One such experience is shared below.

The sports days we organized helped sangha women reclaim male-only public spaces in the village.

The Namma Maathu forums have also led to action on issues that women’s collectives identified as a joint priority for action. In Kalihundi and its neighboring villages, sangha women spoke about impediments to girls pursuing higher education due to lack of bus connectivity. With the support of panchayat members, they launched a local-level campaign, demanding a bus service to their village.

The connectivity problem was made evident by a recent incident. Typically, the area faces heavy rains and flooding. Following one such heavy spell of rains, a few girls found themselves stranded on their respective campuses after school hours as buses stopped plying in the area. We took it upon ourselves to gather villagers who had bikes, and arranged for them to go to these schools and transfer the girls back home. Almost three girls had to sit on a single bike at the same time and the men had to make multiple trips.

Learning dialogues with adolescent girls and boys

The Prakriye team also organized digital media-supported learning dialogues for 350 adolescent girls and 350 adolescent boys from the project area. With support from local schools, the dialogues were organised as a series of classroom sessions and interactions. There were separate sessions for girls and boys to allow candid discussions on gender and patriarchy.

Adolescent girls who participated in our digital media-supported learning dialogues were able to negotiate their rights effectively in family and community settings.

The learning dialogues enabled 23 girls from the villages of Jakkalli and Thumbasoge to pursue their dream of a college education. Inspired by ideas of girls’ rights to mobility and self-determination that were discussed during the training sessions, the girls, with the support of the Prakriye team and the infomediaries, convinced their parents to let them attend college in Mysuru. Of the 23 girls, eight now stay in college hostels, while the rest travel from their homes on a daily basis.

The learning dialogues also helped the girls question myths and taboos associated with menstruation, and sexual and reproductive health. The training sessions enabled them to shed their inhibitions and discuss reproductive health-related issues with parents and teachers. Girls from the Hebbalagupe village submitted a written request to their elected female representative to put in place a sanitary napkin disposal system in their school.

In addition to the classroom sessions, one-day exposure visits were organized for adolescent girls to the local panchayat, Department of Social Welfare, Department of Women and Child Development, and Santwana helpline in order to build awareness on public institutions and welfare entitlements. After an initial round of interactions, many girls felt emboldened to visit the panchayat for necessary services such as processing scholarship applications, obtaining domicile certificates and other documents for processing applications to schools and colleges etc. They have also begun to stay in touch with the infomediaries in their areas to receive public information updates.

The learning dialogues with adolescent boys were focused on communicating ideas of gender equality and respect for women and girls. With inputs from faculty and students of the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, the training modules were designed around deconstructing hegemonic masculinities. The resource material included games that questioned gender stereotypes and pushed boys to challenge their assumptions about the role and status of women and girls in the family and society.

In December 2019, we organized a Gender and Technology fest to create a fun forum to spread awareness about gender equality among adolescent girls and boys, through video screenings, internet-supported activities and simulation games. 400 adolescent girls and boys participated.

IVR serial ‘Anjali Akka’

We developed and launched a IVR serial in fiction format to promote progressive narratives of gender in the local community and catalyze conversations on zero tolerance for gender-based violence. The lead character, Anjali Akka (elder sister), is based on a young woman from a village in the Mysuru region who has assumed an active leadership role in her community with respect to fighting gender-based violence. She is one of the few women in her village who has completed a degree and made great use of her education. An active member of the sangha, Anjali actively speaks up about issues such as women’s empowerment and education of the girl child. In fact, she volunteers to teach the women and girls in her village. She also participates in the ward sabha meetings, where she encourages discussions on these issues. Her husband and family’s support has helped her challenge rigid patriarchal norms.

Each episode of the serial focuses on a range of specific issues – from a husband who is suspicious of his wife for working late, to the newly married young girl who acquires the courage to speak up against her abusive husband. The choice of a fictional format was useful in opening up difficult conversations with community members. The weekly broadcasts of the serial reached a total of 646 women and 251 men in the project area.

An example of an IVR recording is given below:

Outcome 3: Community commitment for challenging gender-based violence in all its forms

From the start of the programme, we were cognizant that the support of influential male leaders of the concerned villages was crucial for the success and long-term sustainability of the project. As the project progressed, it also became evident that large group meetings with elected male representatives, influential caste leaders and village elders were often difficult to convene and not conducive to critical dialogue and discussion, due to caste hierarchies. Over time, we revised our strategy and opted for one-on-one interactions and small group meetings to reach out to over 185 male representatives.

In these encounters, we focused on slowly dismantling their patriarchal perspectives and enlisting their support in the fight against gender-based violence. Our efforts met with success. It was evident that up until these conversations, the majority of men we spoke with had not perceived domestic violence as a problem. In their view, an occasional beating was part and parcel of a woman’s life. Questioning this normalization and naturalization of violence took many rounds of conversations. Certainly, not all men who participated in these discussions could be won over. But those whose perspectives shifted have since become firm friends of the programme.

Some male leaders have supported efforts by sangha women and adolescent girls to make women’s safety and mobility as well as health and sanitation critical priorities in mahila gram sabhas and makkala gram sabhas (the latter are children’s village assemblies mandated by law in Karnataka). Issues of women’s safety in public spaces, allocation of the infrastructural budget for girls’ toilets in local high schools, and the lack of safe public transport options became important agendas of discussion in these forums.

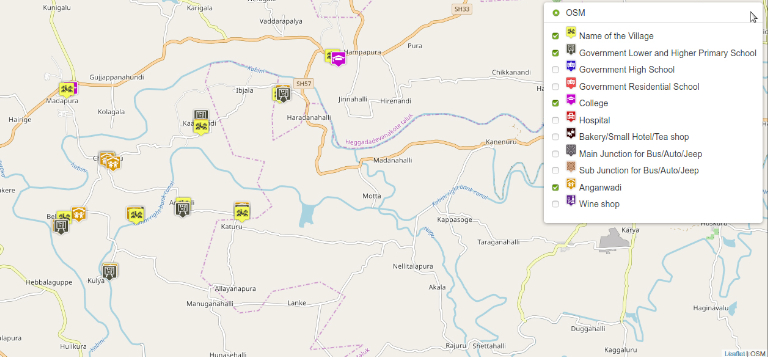

We also worked towards reviving the five-member social justice committees, that each panchayat is mandated to set up. It works on various social issues such as issues of public transport or safety of women and children in the villages. When interacting with panchayat members, we realized that many were not even aware of the need for the existence of this committee. Additionally, committee members themselves had little interest in working because the work was pro bono, meaning, they did not receive any income for this. Through the course of the project, we particularly engaged in discussions with the committee members from the Naganahalli panchayat who had earlier done good work on the committee before waning out. They took interest in our work against domestic violence and took the lead in assisting women in these cases. They also provided support during GIS mapping of the public infrastructure in the village of Dasanpura, which was part of a safety audit conducted in the village.

Besides Dasanpura, we conducted safety audits in six villages in the outreach area of the Kalihundi information centre. These audits focused on the health and safety of women, and examined whether the villages had the required infrastructure to support these issues. We focused on public transport in particular. For each village, we mapped the distance from the nearest bus stand, isolated areas, badly-constructed roads and the lack of street lights – all of which play a pivotal role in the safety of women and girls.

We shared the results of our investigations with the panchayat and took further action based on the discussions that we had with them. The women drafted a letter and presented it to the Panchayat Development Officer (PDO) and local MLA, requesting them for immediate action to improve bus connectivity in the area. Impressed by the solidarity and collective organizing abilities of the women, the local MLA issued an order to the manager of the state transport depot in H.D.Kote to alter bus schedules accordingly.

Our work demonstrates that addressing violence against women and girls is first and foremost about overturning the social norms that naturalize gender subordination. The patriarchal assumptions that underpin family and community mediation of cases of gender-based violence must be completely discarded. To quote one of our infomediaries involved in the project, “Violence is a public problem, not a private shame”. In first phase of this project, we pursued strategies for training adolescent boys and girls in critical gender perspectives, holding media-supported community dialogues, and organizing public events to make panchayats cognizant of their responsibility for promoting a culture of zero tolerance for gender-based violence. But there is far more to be done in terms of promoting a new discourse on women’s rights and gender equality in the local public sphere, and this will be a critical area of focus in the next phase.