ICTs for Teacher Professional Development

The 'Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in education' space appears to be in a transition mode – till now, the default has been to uncritically accept the expertise of technology vendors, and public education systems have usually outsourced the entire processes of developing curricular resources and transaction to these vendors. The main agent in these programmes has been the 'computer faculty', a poorly paid, ill-equipped person, with some superficial knowledge about computers rather than any grounding in education. This has isolated the school system from meaningfully engaging with ICTs and has led to the failure of such programmes, with the education system unable to benefit from the large and exponentially increasing investments in this area in terms of any real impact on teaching-learning processes or outcomes. We are now increasingly witnessing 'second-generation' ICTs in schools programmes, in which the programme design and implementation is being done by teachers and educationists, keeping in mind larger educational aims over narrow technology literacy goals. Such programmes duly consider the educational contexts as well as principles of curriculum and pedagogy, and have been able to obtain the ownership of schools and the commitment of teachers to integrate digital processes and methods into their own professional development as well as in their transactions with students. These programmes support the agency of the teacher and the learner, by enabling a social constructivist digital environment founded on the use of free software and digital content.

During the last few years, IT for Change's work in education has included research to develop a deeper understanding of ICTs in education, teacher capacity-building on techno-pedagogical processes, piloting demonstration projects with schools and policy advocacy. Based on our learnings from this work, during 2011-2012, IT for Change was able to work on a systemic 'ICT in education' model in teacher education, an area identified as very important and challenging in school education. The National Curriculum Framework for Teacher Education 2010 (NCFTE), a landmark document in teacher education, seeks teacher education models that are self-directed, self-paced, peer-learning-based, mentored and continuous. Our work, through the 'Subject Teacher Forum' programme (STF) in collaboration with the Rashtriya Madhyamika Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) programme of the secondary education system in Karnataka, sought to make this vision a reality through a programme design that empowers teachers system-wide; using ICTs to access, create and share curricular resources and to network with one another for 'sharing and seeking'.

|

|

| Radha and Roopa, teachers in Bengaluru, exploring Geogebra, a public software educational tool |

We foresee that many features of this model would integrate into the mainstream in-service teacher education programmes of the public education system.

This year, apart from the STF programme, our main areas of work have been:

- Deep engagement with select schools on building teachers' communities of learning

- Capacity-building of teacher educators and NGOs working in education

- Conducting research

-

Using learnings from our research, capacity-building and programmatic work for policy advocacy

Systemic Teacher Professional Development Model

We conceptualised and designed the STF programme, along with RMSA Karnataka, to provide training and support in the use of digital tools and processes to empower teachers, use public software educational tools to advance their own subject understanding, engage in discussions about their discipline, participate in an online community of learning, and create and share open educational resources. The programme spanned over 800 high schools where ICT facilities have been provided by the government, in 14 districts of Karnataka. We conducted workshops at the state level, to develop 240 high school teachers as resource persons (80 each in Mathematics, Science and Social Science), who subsequently trained around 2,000 teachers from over 800 schools, through an 'enhanced cascade' model. The workshops' curriculum included computer skills, basic web 2.0 skills and public educational software tools relevant to their subject, as well as discussions relating to National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005i position papers and the possibilities enabled by digital processes for supporting constructivist teaching-learning.

|

|

| Director RMSA, M. N. Baig interacting with participants via video conference in a cascade workshop at the Kodagu DIET, from his state office in Bengaluru. |

The workshops with teachers were complemented by interactions across virtual platforms, comprising mailing groups (http://groups.google.com/group/mathssciencestf and http://groups.google.com/group/socialsciencestf) and a web portal (http://RMSA.karnatakaeducation.org.in) where teachers connected to one another to share resources, discuss core teaching-learning and related topics. The teachers were also able to understand and engage at a deeper level with the philosophy of constructivism that has been espoused by the NCF 2005 and the possibilities offered by developing ICT-related capabilities. For many teachers it was a novel experience to create their own contextual digital resources in the local language. The cascade programme involved the high school resource persons trained by IT for Change, working with their colleagues in the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET) computer labs in their districts. The resource persons stayed in contact with the IT for Change team before, during and after the cascade training through the mailing list and web portal, to share resources for the training and information about the participants/contexts, collate and share feedback about the training, and used this to dynamically plan their own training programmes.

There were two unique features about this cascade: Firstly, a large scale ICT programme on a cascade model was implemented fully in-house, using DIET ICT infrastructure and school teachers as resource persons, whereas traditionally ICT training is typically entirely outsourced. Secondly, the fear of 'cascade dilution' was proven to be largely unfounded; with regular interactions amongst themselves and with the IT for Change and state RMSA teams, the resource persons in many cases were able to do a better job (due to their higher contextual understanding) with transacting the curriculum. Thus the cascade model of teacher education is not inherently a weak model, however it is not possible to provide the intensive support it needs without the use of digital networks and resources. Hence, to improve the cascade model that is typical in most in-service teacher education programmes, teachers and teacher educators need to be enabled to use ICT infrastructure effectively than rely wholly on external vendors. This kind of systemic capacity has important implications for enhancing the quality of in-service teacher education.

The virtual learning interactions continued beyond the resource persons, to cover the teachers trained in the cascade. The mailing lists set up in June 2011 had crossed the 3,000 email count by March 2012, belying any apprehensions that teachers would not take to the new virtual medium of interaction. Sharing existing and created resources, asking questions relating to academic issues, supporting and guiding peers in learning to become comfortable in the new digital methods of teaching-learning, can all be seen in these interactions.

|

|

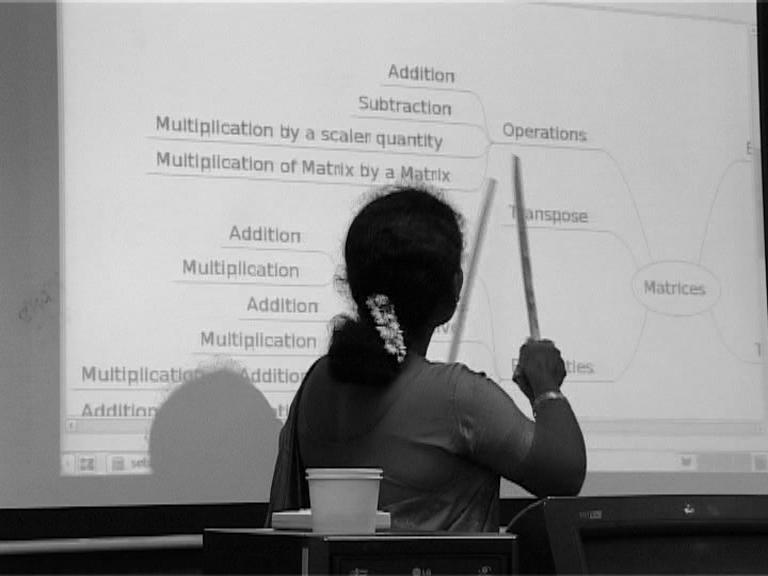

| A teacher using Free mind, a creative thinking tool , to explain Mathematical concepts. |

With support from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) we made a film titled 'Transforming Teacher Education with Public Software' to convey the core principles of our intervention in the STF. The main idea behind the film is to enable policy makers and administrators of other states in India, and also other countries, to get a clear idea of the principles and processes involved in adopting public educational software in their public education systems. The film consists of workshop footage and interviews with teachers and key actors of the programme and can be accessed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D-kgSW_o9z8. We also prepared a 'Public software tool kit for teacher education', which can support a similar programme in other locations. While the STF programme was an extensive one, seeking to bring together all high school teachers (with access to ICTs) across Karnataka, IT for Change also engaged with a more intensive programme; 'Teachers' Communities of Learning' (TCoL), with select schools, allowing for regular interactions with individual teachers. With support from Cognizant Foundation, we worked with model primary schools in Yediyur and Weavers Colony, high schools in Begur and Nelamangala (all Bengaluru) and Mallupura (Nanjagud). In this intensive model, we were able to work with all teachers in these schools on various techno-pedagogical aspects relating to basic technical skill building, creation of digital resources and integrating ICTs into classroom transactions. Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) has an annual 'National Award for Innovative Use of ICT in Teaching', and the work done by Radha Narve and Rajesh Y. N. from Begur and Mallupura schools, respectively, integrating ICTs into the teaching learning was submitted by DSERT, in the government schools category for 2011-2012.

An important learning is that once teachers feel comfortable with various techno-pedagogical possibilities, through using several software applications and utilities, accessing multiple educational resources, and connecting through virtual networks, their creative thinking and keenness to explore is strengthened. This, we find, is in contrast to teachers being seen as 'users' of very few proprietary software applications or specific pre-packaged content, wherein their agency can get restricted. In other words, providing a rich digital environment and strengthening teachers' capabilities to engage with this environment on their own terms appears to provide a strong foundation for teachers' professional development and agency.

For the education system as a whole to begin this process of adopting digital methods, resources and tools, to understand the philosophy and the pedagogical imperative of public software, and the significance of accessing and creating open digital resources, actors other than teachers need to be engaged with. We had opportunities to engage with teacher educators, Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) members, policy makers and education administrators during the year.

|

|

| Manjula, a teacher of government model primary school, Yediyur, creating a solar eclipse simulation using 'Stellarium' and making a video of the simulation using 'RecordMyDesktop'. |

We worked with Centre for Leadership and Management in Public Services (C-LAMPS) to integrate ICT processes into two of their Education Leadership and Management (ELM) programmes. One was the Kalika Balaga (community of learners) programme with teacher educators from DIETs and Block Resource Centres (BRCs) across Karnataka. The second was the Samartha programme of the Karnataka Jnana Aayoga (KJA) and Department of State Educational Research and Training (DSERT), to empower teacher educators and enable DIETs to become decentralised lead resource institutions. In both programmes, IT for Change designed and conducted workshops where participants used digital methods for collaborative construction of knowledge (Kannada commentariesii on NCF 2005 position papers in Science and Mathematics were also developed). The workshops for teacher educators and administrative staff of the DIETs included developing basic technical skills, web 2.0 skills and creating digital resources integrating public educational software tools. We also conducted capacity building workshops for NGOs working in education including American India Foundation, Concerned for Working Children, Makkala Jagriti, etc.

Microsoft Academies in Karnataka

Microsoft had entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with few state governments, in which the curriculum is restricted to their proprietary software applications. Along with our network of educationists, we have argued that such arrangements use public funds to promote the proprietary software of a dominant vendor, which is inherently against public interest, and how instead, the education system could easily create the same infrastructure (comprising simply of computer labs), to train teachers on public software tools, which could be freely shared with them during training. Such free sharing is prohibited by the proprietary software vendor. In Karnataka, on the expiry of the MOU with Microsoft, these academies have been taken over by DSERT to create in-house infrastructure for systemic ICT-related capacity-building.

IT for Change supported the curriculum design, development and faculty training for these academies on public software platforms and a variety of public educational tools and utilities. The curriculum has moved beyond mere office suite to a range of public educational tools, contextualised to the needs of staff in different roles. The earlier model was a significant market creation programme for a single vendor, while the large number of tools now used in the capacity-building programmes of the new 'eVidya academies' are all freely shareable, promoting an environment of learning and sharing. This model could be used by other states with similar restrictive MOUs with proprietary software vendors. The danger from locking-in the large education system into proprietary offerings is not restricted to Microsoft alone – we see many monopolistic product vendors offering 'sweet deals' in the form of 'free training' to the education system. The costs to these companies of offering 'free training' is a fraction of the licence fees extorted through creation of a monopolistic environment, whereas investing a fraction of the licence fee amount on capacity-building and software enhancement would support universal access as well as participation, both educational imperatives in themselves.

Curriculum Development

IT for Change has been invited to participate in various formal work-groups dealing with curriculum design and development for integrating ICTs into education. We have participated in the MHRD Committee to draft new guidelines for revised teacher education scheme for the 12th five year plan of India and coordinated its 'ICT and Teacher Education' sub-group, participated in the National Council for Teacher Education (NCTE)iii Committee on 'Distance Education and use of ICT in Teacher Education', and the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) committee for Quality Education. The aim here is to incorporate ICT education in teacher education as well as classroom learning in an integrated manner. At the state government level, we are a part of DSERTiv ICT curriculum committee and DSERT pre-service curriculum revision committee. We were also invited by Andhra Pradesh State Council of Educational Research and Training (SCERT) to be a part of developing their Social Science and Geography textbooks, and were part of a Geography resource book development project of Eklavya.

Research

We are participating in the Tata Institute of Social Sciences research project - 'Collaborative Action Research on Resource Centres, their influence and impact'. The project aims to understand how teacher resource centres have been working. Our role is to support an understanding of how ICTs could be integrated into the functioning of resource centres, as well as using ICTs to analyse data about the functioning of these centres, including profiling users, patterns of usage of resources etc.

Policy Advocacy

IT for Change also made formal presentationsv on the adoption of public software in education to senior policy makers in the central government, to the Joint Review Mission (JRM) of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (SSA), to Education Secretaries in a MHRD workshop on guidelines for ICT@School programme (which is a large centrally sponsored scheme for promoting ICTs in school education) and to the SCERT directors in a MHRD workshop on the role of ICTs for Teacher Education.

|

| English teacher Gnana Jacob from government model primary school in Yediyur showing her students educational tools for English learning. |

Our advocacy work over the past four years has been able to influence the National Policy on ICTs in school education policy. The third draft released by MHRD in February 2011 included most of our suggestions given as feedback to the original draft, but the clause favouring Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) had been dropped. In a short period of a week, we were able to share feedback, endorsed by 66 eminent educationists across the country, with MHRD, that proprietary software is inherently harmful on pedagogical considerations. Proprietary software (and content) vests the control of important curricular resources with private vendors, denying teachers and learners the ability to freely modify, share and collaborate in learning processes. The fourth and final draft, adopted, in March 2012 as national policy by Central Advisory Board of Education (CABE), an advisory body to MHRD, included in its clause on software a specific recommendation favouring the use of FOSS. The sub-committee, set up by CABE to study the issue of 'vendor driven ICT policy and programmes', also unequivocally pointed to the dangers from large technology vendors intent on creating a market for their proprietary products (both software and content) and the imperative of adopting digital resources that the education system can own and shape in public interest.

However, despite these two documents, state governments are still continuing their legacy habits of prescribing proprietary software platforms and applications in their syllabi and their procurement documents. We wrote a letter, endorsed by educationists, to the Maharashtra and Bihar governments on the need to avoid such specification. There is a clear need to engage with state governments all over the country to help them understand that adopting free and open source software in education in their syllabi and tender documents respectively is a pedagogical imperative, and an eminently practical process as well. Our film as well as the public software tool-kit can support any state government to adopt a programme similar to that in Kerala or Karnataka.

Looking Ahead

During 2012-2013 the STF programme will expand to cover Mathematics, Science and Social Science subject teachers in high schools (with computers) in all 34 educational districts of Karnataka. Additionally, language (English, Urdu and Marathi) and Art teachers will be trained and their subject teacher forums will also be created. We also plan to have a similar programme to create head teacher forums. Creation of local technical support infrastructure for public software will be continued, including training the DIET and BRC faculty on providing techno-pedagogical support to teachers.

While our work has focused on in-service training, during 2012-2013, we will extend our involvement to pre-service teacher education. We are working with the committee set-up by DSERT, on ICT integration into all subjects in the DEd. curriculum revision processes. We will also be working with elementary school teachers, in the Karnataka Computer Aided Learning (CAL) programme of SSA, focusing on ICT integration into middle school Mathematics. The 12th five year plan offers significant opportunities to teacher education institutions, and we will continue our work to develop systemic models for integrating ICTs in the public education system in Karnataka. We will also respond to requests from states, which have evinced interest for a similar programme. Our TCoL programme will continue with support from Cognizant Foundation in Bengaluru, from Sir Ratan Tata Trust's 'Kalike' programme in Yadgir and from Azim Premji Foundation's 'Child Friendly Schools Initiative' in Surpur. Both Yadgir and Surpur blocks are in the socio-educationally backward Yadgir district.

IT for Change has been asked by DSERT to write the ICT text book for the ICT@Schools phase 3 programme. Our design for this textbook goes much beyond ICT literacy and focuses on computer aided teaching-learning. The aim is to make every subject teacher own the computer lab in the school by integrating ICTs into regular subject teaching-learning. IT for Change has also been invited to become a member of NCERT committee for the development of ICT curriculum for schools from classes six to twelve and to a second committee for developing science curriculum for elementary science education.

iThe National Curriculum Framework 2005 is a document published by NCERT, India, which provides the framework for making syllabi, textbooks and teaching within school education in India. (see http://ncert.nic.in)

iiKannada commentaries on NCF 2005 position papers of Science and Mathematics can be accessed from: http://karnatakaeducation.org.in/

iiiNational Council for Teacher Education is the apex national body for teacher education. NCTE prescribes curriculum for teacher education, establishes assessment and certification for TE institutions etc.

ivDSERT is the SCERT of Karnataka, the apex state level body for curriculum design and teacher education

vAll presentations are available on: http://ITforChange.net/Education