Prescriptions for women’s empowerment in the dominant rhetoric

Global and plurilateral trade negotiations are currently suffused with over-optimistic readings about the promise of the digital revolution for women’s economic empowerment. Unlocking the transformative potential of digital technologies is viewed as a simple matter of building the capacity of women’s Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) to participate in global value chains – strengthening their access to digital and financial services, infrastructural support and mentoring – so that they can seize the opportunities in the digital marketplace. In this view, a gender-inclusive trade paradigm is predicated upon trade rules that steer clear of protectionism. Achieving gender inclusivity depends on the unqualified adoption by developing country governments of the following set of policy proposals for a global e-commerce regime: (a) reduction of import duties in cross-border digital trade in goods, (b) permanent ban on customs tariffs on electronic transmissions, (c) prohibition of mandatory source code/algorithmic disclosure requirements on transnational digital corporations, (d) enhanced market access and national treatment for digital service providers, (e) adoption of an unrestricted cross-border data flows regime.

Gender analysis of the current e-commerce model

Emerging evidence suggests that the hyper-enthusiasm around these proposals is misguided. In fact, they reinforce the same model of unbridled globalization that feminists have long been critiquing for its pernicious effects on women in the global south. They are likely to lead to the following negative impacts.

Erosion of the revenue base essential for underwriting care infrastructure

In the global south, a majority of women work in the informal economy and lack employment contracts, legal rights and even a living wage. Under the circumstances, public investment in care services (for children, sick, elderly and disabled) and care-relevant infrastructure (social security net, health and sanitation services) becomes non-negotiable for alleviating women’s triple burden. This is possible only by strengthening the fiscal revenue base. Trade tariffs are a very important source of tax revenue for developing countries. In the global cross-border e-commerce marketplace where a majority of developing countries are in the position of net importers, any increase in the de minimis thresholds or a permanent ban on customs duties on electronic transmissions will contribute to a significant tariff revenue loss and erosion of the fiscal resources of developing countries. This will directly result in a cut in welfare and social security budgets, and as research across the world has shown, shift the burdens of care work onto women.

Precluding ability of governments to address algorithmic discrimination against women

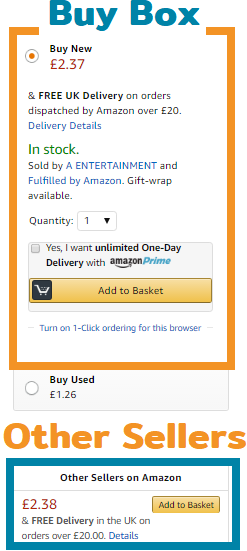

In the platform marketplace for goods and services, algorithms match customers with producers/ service providers, rewarding top-ranking suppliers with heightened visibility while obscuring others. Evidence suggests that the criteria used in such algorithmic evaluation ends up unfairly excluding and marginalizing women-run small businesses and women workers associated with service platforms. Consider Amazon’s ‘Buy Box’ algorithm - the white box on the right-hand side of the product detail page where Amazon suggests the default seller for a particular product line. Since 82% of sales accrue to default sellers pushed by ‘Buy Box’, winning this slot is vital for business survival. Though the algorithm itself is closed to the public, certain seller performance metrics are known to be key: competitive pricing, free shipping, low product defect rates, responsiveness to customer communication, and product stock levels maintained with the platform. Considering that the majority of women-led enterprises in developing countries are small size businesses with low output levels, limited growth potential, thin price margins and very little capacity to bear inventory and customer service overheads, they end up being perpetually disadvantaged in such data-based scoring processes. Research also reveals that on-demand domestic work platforms in the global south end up using discriminatory demographic criteria such as marital status, religion, caste etc. in their demand-supply matching processes.

Course corrections are possible only through public scrutiny and audit of these algorithms and measures to institute scoring criteria for affirmative action where necessary. By waiving off the right to demand disclosure of algorithms/source code in e-commerce negotiations, developing country governments are essentially giving up their right to regulate against unfair discrimination and in favour of gender equality.

Deregulation that ignores digital restructuring of agriculture

The emergence of new platform business models has led to a situation where the traditional classification between agriculture, manufacturing and services has become blurred. For example, farm-to-fork business models have seen the introduction of data-related services in every aspect of agricultural production: input advisories, real-time tracking of agro-climatic conditions, logistics management systems covering every step from aggregation of produce and price forecasting to last-mile retail delivery. Research undertaken by IT for Change in Africa suggests that by making agricultural practices of farmers more legible to financial service providers and agricultural companies controlling agro-commodity markets, these models serve the interests of big players rather than meet the knowledge and productivity enhancement needs of small farmers. Platform models capture local agriculture by displacing traditional value chains and orchestrating a closed environment where inputs, credit, logistics and markets are centrally controlled. This could result not only in a loss of local autonomy, but also an erosion of subsistence based livelihoods of women farmers. Developing countries need to institute policy measures in this emerging context to protect farm-based livelihoods of women. However, under the current trade paradigm, developing countries face several dilemmas; How should market access and national treatment obligations accepted under General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) be applied in platform models? What service liberalization commitments apply? Should developing countries be penalized simply because the GATS was negotiated in times that were pre-digital? It is only logical that service liberalization commitments must be re-negotiated for new digital business models. But powerful countries have been blocking this move and trying to bring in widespread deregulation of key sectors by arguing for the application of ‘technological neutrality’ to GATS commitments. This must be resisted firmly, as otherwise, countries of the global south will have no wiggle room to reverse the intensification of economic concentration and the skewed distribution of value in the rise and rise of the platform economy.

Loss of the right to create digital public goods for women’s economic empowerment

Opportunities for women’s entrepreneurship and economic participation in the digital economy depend on new investments in digital industrialization. Governments need to create data and platform based public goods - public data sets and big data tools to incentivize local digital start-ups, online marketplaces that promote women producers/ micro-entrepreneurs/ artisans/ service providers and so on. Similarly, they must revitalize and strengthen public services and institutions through intelligence-based digital tools to enhance gender-based inclusion and the quality and efficacy of reach. Both these types of initiatives are predicated on building a robust public data commons, tapping not just into data sets generated or held by state agencies, but also through access to aggregate, de-identified data sets held by private platform companies working in different sectors. Without the power to institute mandatory data localization, developing country governments will find themselves held hostage by transnational digital platforms. Valuable data resources of societal systems and institutions will be captured by transnational digital companies, while government interventions in the public interest and towards gender equality will be forestalled by lack of access to data generated within their jurisdiction. Considering that even in the partnership between Deep Mind and the UK National Health Service, this has been a problem, it would augur well for developing countries to be agile about the real implications behind the rhetoric of free data flows.

What next for governments in the global south?

Developing countries need to call out powerful governments for their double standards; pursuing their own pathways to digital industrialization, while dismissing the claim of developing countries to preserve the domestic policy space for making good the opportunities of the digital era. Prescriptions to join the e-commerce bandwagon piloted by big digital corporations with more mentoring, access to digital infrastructure and finance for women is likely to make no dent in the systemic exclusions that prevent women’s equal participation in the economy. It may at best bring some benefits for a few women, and at worst sabotage the interests of the majority of women. Developing countries need to come together to hold firmly onto their right to regulate digital trade, rejecting the dominant policy rhetoric preventing selective liberalization of tariffs in cross border e-commerce, mandatory disclosure/sharing of algorithms and source code, imposition of market access conditionalities and local presence requirements on transnational digital corporations, and introduction of data localization measures. The democratic deficit in rule making about e-commerce and the red herring that women’s empowerment becomes in pushing the interests of powerful corporations and rich countries are but two sides of the unjust trade coin. The hyper-liberalization of digital trade and its hard-coding into binding rules through multilateral/ plurilateral processes can be more grievous and devastating for women in the global south than in any other previous round of trade globalization. Developing countries must act now to protect and promote women’s economic citizenship in the age of data.