on the send-off of Sri Jayakumar, Director DSERT at Kaveri Hall, on April 11, 2016 - Gurumurthy K1

Sri S. Jayakumar (SJ) was the director of DSERT for around one and half years. Within this short period, he was able to make a deep impression on his team as well as others who interacted with him. One way of understanding why he was able to make such impression, and also of paying tribute to his work at DSERT would be to share some reflections, from an Education Leadership and Management (ELM) perspective - exploring aspects of individual, institutional and systemic leadership in the Indian education context2. A caveat; I have based these reflections on my interpretations of some limited interactions with SJ; hence this note by no means is a comprehensive analyses of his leadership, or a manual on ELM.

Table of Contents

1.1 Combining positional and personal power

2.1 Educational reform, a plant of slow growth

2.2 Institutional memory and institutional learning

3 Systemic leadership- Strengthening teacher education

1 Individual leadership

The first thought that comes to my mind about SJ is his ability to consistently relate to his subordinates in a humane manner, treating them as allies. The bureaucracy has ‘strong’ leaders, who communicate their authority in harsh ways. By contrast, it is very rare for SJ to lose his cool, shout in anger or frustration, or be insulting and demeaning. It was aptly mentioned by Gangamare Gowda sir in his send-off remarks, that while we could usually hear our heartbeat when taking a file for approval to a senior officer’s chamber; in SJ’s case, we could go in with the full confidence that the quality of our points would decide the issue, not his mood! SJ would say in semi-jest that his name was S. Jayakumar, so he was always inclined to accept his officers’ suggestions and proposals (“I am S (Yes) Jayakumar”). This is a measure of the enormous trust he reposed in his officers. ELM literature talks about trust as the foundation for a collegial and performing environment and SJ was greatly able to inspire people around him, by simply trusting them and supporting them to do their best.

IT for Change as the resource institution for the Subject Teacher Forum (STF) program, has been working closely with DSERT. A large program like the STF continuously faces challenges and obstacles. Anytime there have been issues needing his attention, SJ has been aggressive and proactive in addressing them. On many occasions, he would insist that I sit in his room and not leave till all issues were resolved. Issues, which in my view, would have normally required multiple visits to DSERT over days and weeks, were resolved in a single day; file notes made, letters prepared, calls made and decisions taken. And while he took decisions that he needed to take to resolve tricky issues, he was also conscious that his officers should be empowered to do what they needed to. ‘I hereby make you the director, please do all that is required to be done’ was not an uncommon refrain to his officers, telling them clearly that they could go ahead and do what was needed to be done and he would be firmly with them and behind them. Not only was there no fear or apprehension in entering his office, instead there was an assurance that the discussions would be frank and friendly, creating an environment of joyous working.

A thought here, our schools cannot be sites of ‘joyous learning’, if our academic institutions are not sites of joyous working. This is usually not the kind of educational leadership emphasised in the government education system, with people stressed due to inadequate comprehension and voluminous responsibilities, coming in the way of creating a productive yet happy environment. SJ’s approach combined both3.

1.1 Combining positional and personal power

An important ingredient of leadership is positional power (authority). In the hierarchical government system, positional power is accepted and used. A director is always ‘director sir’ and his/her orders are taken seriously and attended to, acknowledging the power inherent in that position. Very rarely do leaders go beyond positional power, to create ‘personal power’ which is not based on positional power or authority, but based on earned respect and affection. Personal power can complement positional power to enhance the effectiveness of one’s work (Of course, where personal power is used to further institutional aims and not personal interests!). Such development of personal power and use for the education system’s goals is a distinctive aspect of SJ’s leadership. He was able to command the respect and affection, not only of all the officers who reported to him, but people far and wide in the education system and beyond.

When Prof. M. K. Sridhar, member of CABE (and earlier director of Karnataka Knowledge Commission) wanted to interact with people working in Karnataka education, across levels and geographies, to take inputs to CABE, SJ organised an interaction meeting on a Sunday. There was nothing ‘official’ about this; as he said “Sandesha kalisidini, adesha illa” (only a warm invitation, no formal orders to attend from DSERT and no TA/DA). But everyone invited came (not only from Bengaluru, but from all across the state). On a Sunday, for department officials and NGO members to happily and willingly come, to share ideas for improving the education system, is something extraordinary and unique, reflecting SJ’s personal power. Routinely, officers of DSERT have stayed beyond office hours to accomplish what they all saw as important or necessary to get done.

2 Institutional leadership

In an institution, less effective functioning can be caused due to low initiative of the staff, as well as the low level of alignment to the institutional goals. In a large institution like DSERT, sometimes individual officers can feel quite atomised in the work of their section, and be unable to connect to the larger picture of DSERT’s work and mandate. This can reduce alignment of individual officers to the larger DSERT vision and also reduce initiative. Secondly, the absence of consistent communications of reasonably high expectations of officers, can keep the initiative low. Institutional leadership focused on increasing alignment and motivation is termed ‘generative leadership4’. Generative leadership is supporting people to move from low alignment to high alignment and low initiative to high initiative, thus increasing institutional energies and efforts.

This is a very difficult and complex task, something which, we find, most leaders simply not able to devote time or energies to. SJ took this up in full earnest. He attempted to increase alignment of individual officers to the institutional goals of DSERT by continuously sharing the goals, priorities, values with all, in formal (e.g. the weekly Jnanadhara video-conference sessions in which external resource persons spoke on different issues to department officers in DSERT and DIETs, regular team briefings and reviews, inviting NGOs to present their work to the DSERT team, seminars) and informal (e.g. regular free and easy sharing of ideas on various issues with his officers) situations. Increasing alignment through continuous dialogue with the DSERT team helped to make them feel that their ideas too can have a role in DSERT functioning.

SJ insisted on having high expectations from his team, and expected them to take higher initiative, promising all support required. He would not hesitate to point out that he had higher expectations with respect to work done. Thus, by consistently making reasonable (and sometimes unreasonable) demands on people and insisting that they use the authority they had, helped encourage initiative. By declaring his officers to be 'directors' of DSERT, who had the same authority that he had, he suggested that they needed to take decisions to improve the working of the institution and to achieve its goals.

Institutional leadership requires that all people within the institution feel a sense of connection to the institution. For perhaps the first time in the history of DSERT, Group D employees felt that they were being heard, when SJ called all Group D employees for a meeting with the single agenda that they should discuss their issues and the challenges faced that prevented them from giving their best in their work.

I have seen during SJ’s tenure, how DSERT has been able to move up the ladder of low initiative - low alignment to high initiative - high alignment5, in my view, is his biggest achievement as director DSERT. Such institutional leadership, that too of a large institution like DSERT is extremely difficult and rarely seen and his work is a role model.

During the short period, SJ and Smt Chandramma were at DSERT, perhaps the most important achievement was the building of an institutional identity and inter-personal trust in the team. The director – joint director team have tended to gently engage with the team and persuade them as a friend, than direct them as subordinates who need to comply. The ‘talmaya’ (co-operation and alignment) between them has also been remarked upon and appreciated by Krishnamurthi sir in his send-off remarks.

2.1 Educational reform, a plant of slow growth

Michael Fullan 6says, education is a “dynamically complex” process where not only the system consists of complex relationships amongst multiple variables, but the values of these keep changing. Getting a reasonable handle on these variables, figuring out strategies to address challenges and achieve educational aims is a time consuming process. This means any change or reform in education takes a long time to show results, a leader needs to be given a reasonable period of time to vision, create a shared understanding of the vision and work towards the same. Having a minimum tenure of 3 years has been proposed for all leadership positions in the bureaucracy. In its absence, no leader can seriously plan any significant academic changes. Any such complex programs initiated can be in serious risk of being discontinued. If SJ had been given at least a 3 year tenure, we may have seen many significant and complex achievements completed successfully.

2.2 Institutional memory and institutional learning

This is exacerbated by the fact that the government system does not have an effective method of succession. Any meaningful handover would require that both the person leaving and his/her successor work together for at least a week to have a detailed understanding not only of the activities, but also the underlying purpose and principles. However, formal handover interactions seldom go beyond a day. The lack of such handovers can affect 'institutional memory'.

Just as individual memory is an extremely critical part of individual learning, institutional memory is as critical to institutional learning and development. The sudden transfer of leaders, and inadequate time for their handing over of responsibilities to their successors, gives rise to a deja vu “a new leader has come... and we all need to start all over again...”, which is quite frustrating and demoralizing and can damage institutional energies.

3 Systemic leadership- Strengthening teacher education

In a large hierarchical system, like the education department, gaps emerge easily between institutions at different levels in the hierarchy; the district institutions can feel that the state offices are unempathetic and unsupportive, where the supervisors from the state institutions extract accountability through punitive monitoring but are often unable to provide the academic and administrative support required by the district institutions, to enable them to be effective7. The ‘Spandana’ program of DSERT, in my view, is perhaps the most significant and effective program of SJ, as it directly addressed the difficult issue of inter-institutional trust, and contributed to a systemic improvement in teacher education institutions across the state.

In the ‘Spandana’ program, the DSERT team visited the DIETs in the state. The entire team used to travel by bus, often overnight, to visit a DIET, and all DIETs, those far away, as much as those near, were covered over time. This was not a one time wonder, but a periodic event, many DIETs were visited multiple times. These visits helped both DSERT faculty and DIET faculty to understand the roles, priorities and challenges in both institutions and enable an environment of shared understanding of issues.

3.1 Networked leadership (connecting across the system)

Given the multiplicity of actors in the education arena, a leader needs to build networks to enhance his/her circle of influence. One systemic leadership aspect SJ repeatedly demonstrated was to bring people in different institutions and different levels together. He initiated mobile phone groups where members included not only DSERT staff, but also DIET, BRP faculty, teachers, NGO staff, political personalities, and academicians for sharing and peer learning. The diversity of the group was also reflected in the discussions on these forums.

The school – community linkage is acknowledged to be weak in case of government schools and the ‘Shalege Banni Shanivara’ program initiated by SJ, encouraged members of the community to come to the school and teach the children. This program would have raised the hackles of those who believe that teaching-learning is a complex process, and hence any outsider, who is unlikely to be qualified or equipped should not be given a direct entry into the classroom. Yet, in the context of popular perception of opacity of government institutions, the program made the government school more porous, by encouraging people within the local community to come to the school and interact with the teachers and students.

And the process of bringing people together has continued for SJ, even after he has moved to the Vocational education department, with his rejoining the mobile phone community that he set-up. Good leaders are hard to hide, or wish away!

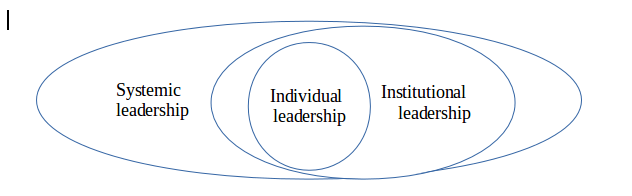

Leadership – spheres of influence

4 Individual-institutional-systemic leadership, a continuum

Institutions can enable individuals to come together and work towards shared goals, institutional effort is far more effective than individual effort. In today’s networked world, bringing together as many diverse actors as possible can enable effective and sustainable efforts at a systemic level, such systemic leadership is an essential part of education leadership. In this article, ELM is seen along the continuum of individual-institutional-systemic leadership, operating at individual / inter-personal, institutional and systemic levels.

1Gurumurthy Kasinathan’s association with DSERT goes back to June 2004, when he joined the Policy Planning Unit (PPU) within DSERT, on deputation from the Azim Premji Foundation. He moved with the PPU to the office of the CPI, and worked there till 2008. He is currently Director at IT for Change, the resource institution partnering DSERT, in the Subject Teacher Forum, in-service teacher training program for high school teachers. He is also a visiting faculty for the ELM and ICT and Education courses in the MA Education program of TISS Hyderabad.

2As a visiting faculty for the ELM (Education Leadership and Management) course, at TISS Mumbai earlier, and now at TISS Hyderabad for their MA in Education programs, I have found limited material on ELM that is based on practice in the Indian education context, so perhaps these reflections can also provide some food for Indian ELM thought.

3Remember another role model here, retired deputy director Sri Thirumal Rao, who combined a high focus on tasks with gentle and quality humor, which made it a pleasure to work with him

4Model used by Erewhon, an organisation working on individual and institutional creativity to solve complex systemic problems. Erewhon was a partner of Policy Planning Unit, in the ‘Pramata’ (Prakriya Manthana, Adhikaraigala Tarbabeti) project of the department

5This is not to say that there was low initiative or low alignment before SJ took charge, rather the situation of alignment and initiative further improved during his tenure, and significantly so.

6 Fullan, M. (1996). Leadership for change. InInternational handbook of educational leadership and administration (pp. 701-722). Springer Netherlands.

7 Batra, S. (2003). From School Inspection to School Support: A Case for Transformation of Attitudes, Skills, Knowledge, Experience and Training. Management of school education in India, 67.