As technology becomes a real and unfragmentable part of social interaction, a global crisis is evident in the form of widespread normalisation of online violence against women (VAW).

It is vital that laws on online VAW draw from the foundational ideas that have informed interpretations of gender-based (in)justice, recognising the immersion of human society in digital experiences.

Equality with dignity

Non-discrimination and equality comprise the cornerstone of legislation on violence against women in both international and domestic laws. We have seen these ideas in judicial decisions across the world. Feminist legal traditions recommend using the framework of ‘substantive equality’ – which accounts for the specific needs of women, rather than of ‘formal equality’ – wherein policies that appear to be non-discriminatory may not really be responsive to the systemic discrimination women face. Gender inequality therefore must be seen as a historical-social experience that erodes human dignity. The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women’s (CEDAW’s) position on discrimination against women, which is seen as an affront to human dignity and equality, is rooted in such a discursive legacy that acknowledges a historical imbalance in power relations between men and women. The model framework for legislation on violence against women, proposed by UNDAW/DESA also interprets violence as a form of discrimination and a violation of women’s human rights.

Harm as a violation of dignity and privacy

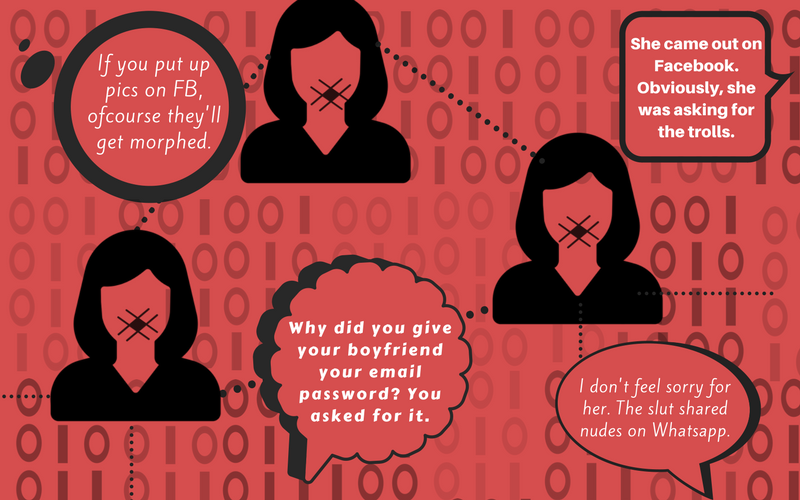

‘Harm’- to the body, mind or both is often seen as ‘proof’ that violence has occurred. The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defines VAW as ‘any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women…’. While most States have sought to protect women from violence, at least in the language of the law, the treatment of harm in many instances continues to be problematic. The Indian Penal Code retains Victorian and patriarchal language, and phrases such as ‘outraging the modesty of women’, continue to feature, despite a major law reform in 2013. This approach of the law tends to put women on the stand for their ‘morality’ to be assessed, adopting a benign protectionism, at best, or condemning women’s ineptitude for ‘attracting harm’, at worst. Similarly, Indian courts’ interpretation of obscenity has fixated on sexual content. The law’s intent on ‘protecting society from depravity’ has ended up treating women as objects that law must govern, rather than as subjects who have the right to legal recourse. A feminist critique would call attention in these approaches to the denial of women’s agency and the disregard of sexist content that may not necessarily be sexual.

We posit the need for an alternate theory – one that addresses harm as a discriminatory act that impinges upon a woman’s dignity and a violation of her right to privacy seen as the triumvirate of bodily integrity, personal autonomy and informational privacy.

Courts have used this progressive theorisation of harm to redress violence against women. For example, the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights found that sexual abuse was not only a violation of physical and mental integrity but also a woman’s dignity. In a case involving the restitution of conjugal rights before the Supreme Court of India, Justice Choudary noted that vacating of a woman’s agency to that of the state is a violation of her bodily and mental privacy and consequently, an affront to her integrity. The European Court of Human Rights, in a case of forced sterilisation of a woman, affirmed her right to personal autonomy holding thatthe perpetrators had disregarded the woman’s dignity, by denying her the necessary information to make a free and informed decision. In NM and Others v Smith, the Constitutional Court of South Africa held in favour of three women whose HIV status had been revealed without their consent. The court observed that ‘the personal and intimate nature of an individual’s health information, unlike other forms of documentation, reflects delicate decisions and choices relating to issues pertaining to bodily and psychological integrity and personal autonomy’, thereby affirming their informational privacy.

Dealing with the here-and-now reality of online VAW

How do we bring these core principles into remedies for online VAW? That the online has become a space of misogynistic and sexist vitriol is undeniable. Seven in ten women have faced online violence against women. ‘Cyber-touch’, as the UN Broadband Commission for Digital Development, puts it, is as harmful as physical touch. Survivors of online violence recount feeling vulnerable and unable to participate in life online or offline. Not only depression, fear and anxiety, but even suicides, among women who face sexual violence online, are routinely reported. The dissociation characterising online interactions is seen to result in disinhibition, prompting ‘toxic’ masculinities, with tangible, corporeal consequences for women victims.

Just as in the case of offline violence, in instances of online violence as well, women experience a breach of dignity and a violation of privacy. This is true when videos of rape are circulated through WhatsApp, or intimate pictures shared by a woman with a man are leaked online by him, or when morphed pictures of women are posted on social media.

CEDAW’s General Recommendation No. 19 and General Recommendation No. 35 acknowledge that freedom from violence is essential for the enjoyment of all other human rights of life, liberty, health, security, etc by women. 74 per cent of countries covered by the Web Index lack an adequate mechanism to tackle online violence against women. Along with failures in law enforcement and justice delivery, current legal frameworks are unable to deal with the nature and extent of VAW mediated through technology.

However, some countries have started taking steps to broaden the ambit of law to include online violence. Methods adopted in this regard include:

- Revisiting pre-digital laws to include online violence – for example, Israel’s amendment of its Prevention of Sexual Harassment Law, to include cases of non-consensual distribution of sexual images online.

- Making additions to laws dealing with cyber crimes in general – usually, gender neutral amendments, as were introduced in India’s Information Technology Act, to criminalise violation of privacy by non-consensual publication and transmission of images of ‘private parts’ of an individual.

- Enacting laws to specifically deal with cyber violence – as in the case of New Zealand’s Harmful Digital Communications Act that treats the deliberate causing of serious emotional distress through messages or posting material (through digital communications) as an offence.

Institutional patriarchies make the due process of justice a long and hard road for women. To get to the goal of gender equality, transformation in the institutions of law and justice is needed. This needs to be agile and iterative. Whether a country chooses to make incremental changes in its existing legislation or enact a stand-alone law, to tackle online VAW may be less important. What is critical, however, is that institutional interventions be built upon the foundations of gender equality – reclaiming women’s rights to equality, dignity and privacy, as the core constituents of just societies in the digital age.

This blog was first published by LSE Women, Peace and Security.