Translation is seen as a high-skilled professional activity, which restricts its reach. Three members of an NGO, that works with government schools, attempted to translate text from English to Kannada, using easily accessible digital tools; the NGO also supported teams of student-teachers and teachers to use these tools for translating education materials. The aim was to make translation a participatory exercise - ‘by teachers, of teachers, for teachers’, and improve education resources availability in Kannada.

(Note - digital tools/methods used are marked in bold+italics in the article for easy reference).

Article was published in the Jan 2021 issue of Language and Language Teaching, Azim Premj University.

2.Resource gap

The volume of materials (articles, papers, media) in English far exceeds that of Indian languages. This can make not knowing English a disadvantage; even though factors like one’s ability (text fluency) and desire to read, affect this advantage.

Wikipedia, the popular encyclopedia contains millions of articles in 130+ languages; English has over 6 million articles while Kannada less than 30,000 (<0.5%). Hindi (1,40,000+) is the highest amongst Indian languages. English is spoken by around 10% of Indians (2011 census). Those who read English, for pleasure, would likely form a much smaller part of this 10%. ‘Reading without comprehension’ is identified by studies and policy documents1 as a common Indian malady. English teaching largely focuses on decoding the script and being able to reproduce memorized content in written examinations than enabling students independently use it for communication or as a tool for leaning.

If we could translate into local language content, articles in English could reach more people. The availability of contextual reading materials is also important in developing interest in reading in young minds. While, the number of children’s literature books/resources published in English is much higher than in Indian languages, translation can be a method to provide greater access to written literature. (Transcribing literature widely available as oral resources is also possible and necessary).

Translating articles on education-related topics would help broaden and deepen the understanding of education. This could promote learning in that language, as well as teacher professional development.

There is a need for translation projects, such as the ‘National Translation Mission’, project of the Government of India, for translating knowledge texts from 69 disciplines into 22 Indian languages2. The Azim Premji University (APU) is translating its English language publications into Kannada and Hindi. IT for Change (ITfC), an NGO working for a just and equitable digital society, is collaborating with APU on Kannada translations. ITfC is also implementing other projects which use the MediaWiki platform for creating and sharing content in Kannada

This article discusses how a team from ITfC used digital technologies for simpler and quicker translation.

3.Complexity of trans-creation

Translation cannot merely replace words from one language with equivalent words from the target language (‘Meta phrase’). Translators must resist the temptation to re-use source language (SL) words in the target language (‘transliteration’); it is necessary to popularize equivalent words in the target language (TL), or create new words that are more reflective of the TL and culture of TL communities. Translation has to bring the text closer to the local culture for meaning-making. Translated resources must be crisp, not elaborate explanations or commentaries on the source text.

Translation is complex; it requires several skills. The translator has to be competent in reading and writing the SL and the TL. She/he has to understand the content in the SL and write it in the context of the TL. This also requires excellent vocabulary, including knowledge of phrases and idioms in both languages to reflect cultural nuances in translation, as well as a reasonably good knowledge of the domain. Articles on Mathematics teaching would need the translator to be familiar with the terms and expressions used in Mathematics, as well as a broader understanding of education, its philosophies and practices.

The process of translation helps readers understand and learn from the culture of the people who speak the SL. It also introduces new ideas into the TL. Sarukkai argues that “when we evaluate concepts across cultures, we cannot be looking for equivalences, but only for the potential to bear possible meanings, what I refer to as ‘meaning-bearing capacity.”3 Shivaprakash4 asserts that translation “requires not formal equivalence but affective equivalence”. The challenge is to capture the essence of the article, which could help a TL reader have experiences similar to the SL reader, yet situating in their own context. Given these complexities, ‘translation’ is sometimes termed ‘trans-creation’.

4.Conventional translation (pre-digital)

In the conventional translation process, a single person typically reads a printed document and hand-writes the translation, referring to print materials (including dictionaries, bilingual dictionaries, thesauruses). The translator verifies every word, phrase, sentence, and paragraph in the SL and identify words, phrases and sentences in the TL that would “bear the maximum meaning”. This requires a single person to have all the skills discussed earlier, a rare occurrence, hence translation is mostly restricted to professional translators.

If the professional is not adequately competent in the cultural nuances of either SL or TL, it could result in sub-optimal outputs. The manual process requiring access to physical resources – dictionaries, reference books can be time-consuming and effort-intensive. Error correction of such documents would be similarly time-consuming. If the professional is not fully conversant with the domain of the article, the translation could contain erroneous interpretations. However, no professional translator can be proficient in multiple domains of knowledge.

While the traditional pre-digital era method severely restricts the number of people who can translate, it is perhaps still predominant.

5.Translation using digital methods - APU publications

Digital technologies increasingly used in translation include Human Aided Machine Translation (HAMT), such as Google Translate and Machine Aided Human Translation (MAHT), such as online dictionaries, which takes lesser time than printed dictionaries (“It is known that the most time-consuming and painstaking part of a translator’s job is turning the pages of a dictionary…”), digital terminology data banks listing special-purpose terminologies, which enhance translation efficiency and accuracy, and translation memories, which are previously translated texts available digitally5. In MAHT, the translation is completed by humans unlike HAMT.

A three-member team from ITfC used simple, easily accessible desktop and cloud-based technologies to translate articles from APU journals from English (SL) into Kannada (TL). The team - T1-Anand, an MA in Kannada and a Kannada language teacher for over a decade’, T2-Karthik, an MA in Kannada with a reasonably good knowledge of SL and TL, having a broad knowledge of different disciplines; and T3-Gurumurthy, with sixteen years experience in and publications relating to education (in SL), who understands spoken TL. Anand’s SL reading/writing proficiency is limited, Gurumurthy’s TL reading/writing proficiency even lesser. All work in school education projects of ITfC, none is a professional translator.

6.Translation process

T1 or T2 completed the initial translation of an article, referring to online machine-translation tools like Google Translate and Shabdkosh, and web repositories like Kanaja and Baraha. Mono and bi-lingual digital dictionaries available online and offline (on computer and mobile phone) were accessed, and different meanings of a word/phrase identified through simple ‘search/find’ processes. Oft-repeated terms used in education were stored in a simple tabular format on another cloud document (Google Sheets) to allow easy reference (‘terminology data banks’ discussed earlier). The team simultaneously accessed both documents.

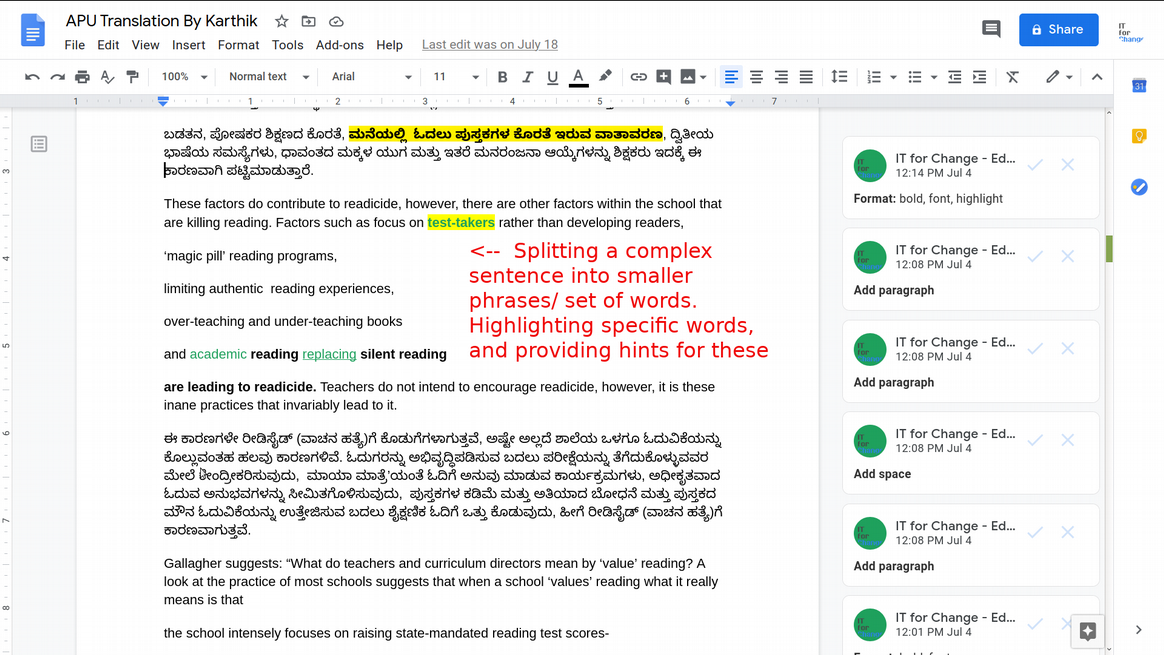

The translator made paragraph-wise sections of the document and provided the TL translation just below the SL paragraph. The digital document became a bilingual document, with the translated section available below the original, for easy comparison.

This document was uploaded as a cloud document on Google Docs6. A common team gmail-id was used by members, to access the same document with full editing rights.

T3 ‘broke’ complex sentences in the source text into meaning-holding units, adding punctuation marks like ‘,’ or ‘-’ or line-breaks, for easier comprehension. T3 used the ‘track changes’ feature of the document editor, by which his additions, modifications and deletions were highlighted, so that T1 and T2 could distinctly identify the original text and the changes made by T3.

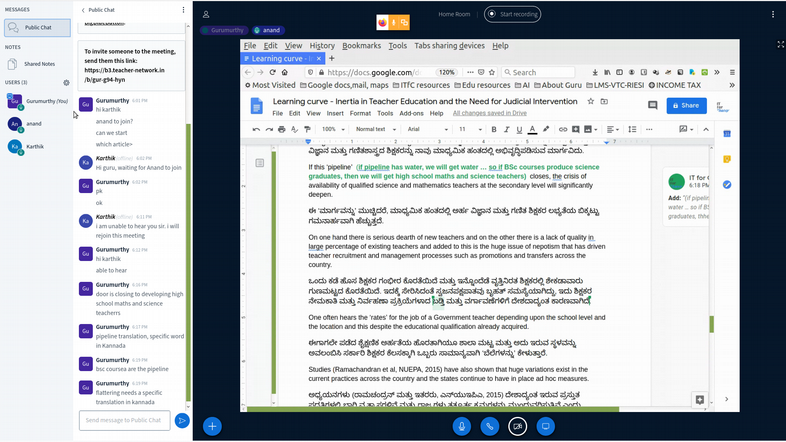

Once the translation was completed, the team met on the free and open source BigBlueButton video conferencing/webinar platform (similar to Google-meet or Zoom) for a collaborative review of the translation. The bilingual document was shared on the platform, using the screen-share feature to help the three members focus on the same section. All also simultaneously edited the Google document on their own computers.

T1 and T2 who worked on the TL text, did direct edits (without using track changes feature, unlike T3), for real-time easy comprehension of the TL document and changes during the discussions.

T1 would read out the content in the TL, and T2 and T3 simaltaneously assessed the quality of the translation. T2 reviewed the flow of the TL text and focused on SL-TL equivalences. T3 checked if the spirit of the SL content had been adequately captured in the TL, and on its appropriateness in the education context. T2 made corrections, as required.

The translation process usually generates multiple interpretations of the SL as well multiple expressions in the TL. Hence, there were differences of opinion on the correctness / relevance of translated words/phrases/sentences, and which of the competing TL versions contained the ‘maximum meaning’ that Sarukkai speaks about.

Whenever these doubts or debates could not be resolved quickly, the team checked translation and other relevant websites for equivalent words in the TL. Pages for the same topic from the Kannada and English Wikipedia were accessed to find equivalent words for the terms being debated. Often, this helped the team arrive at a consensus on the interpretation of the phrase in SL and/or the word/phrase to be used in the TL. Once corrections/changes were identified in the translated text, the words/sentences were edited and revised at the same time by T2, under the watchful eyes of T1.

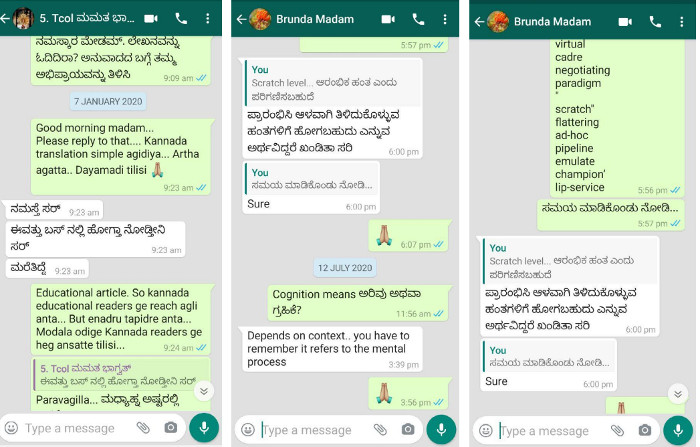

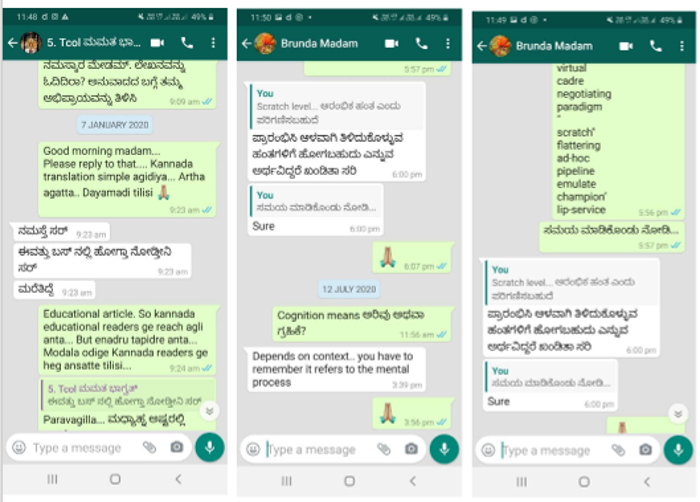

Where the team did not agree, T1 sought help from external experts, by sharing the word or phrase or sentence in both SL and TL through asynchronous social media (Whatsapp). Since Whatsapp Web version was installed on his computer, this required a simple copy-paste from the cloud document to WhatsApp.

Once the draft translation was complete, T1 shared it with a friend in the ‘Kannada teachers’ group (or in case of an ‘At Right Angles’ article, with a Kannada medium Mathematics teacher) for their review comments over mail. Since the translation aimed at providing resources for Kannada language/Kannada medium teachers; their review would help assess if that purpose had been achieved. Thereafter, the translated article was mailed to APU, for publishing on their site.

The subsequent step could have been, to host the article on a Wiki7, instead of (or along with) a static web page, so that readers/teachers could further refine/improve the translation. No translation can ever claim to be complete, this is true for any material creation process. The Wiki symbolises a perennial embrace of people and materials in mutual improvement.

We were able to implement this Wiki process of infinitely iterative improvement in a another translation project of ITfC. Our ‘Wikipedia content translation’ project was a practicum for student teachers of the teacher education institutions8 where we taught the ‘ICT Integrated Learning’ course across the four semesters of their two-year Bachelors of Education programs.

7.Translating to Kannada Wikipedia

The NCERT National ICT Curricular Framework, 2013, discusses ‘connecting and learning’ and ‘creating and learning’ as important themes for integrating ICT into teaching-learning, these are equally relevant to translation. Connecting people can facilitate collaboration amongst diverse participants. Complementing diverse capacities can allow a group to create a translation, which individually none of them could have. Secondly, digital tools enable people to create materials in the TL, which can by itself, be a developmental process. Papert refers to ‘constructionism’ - as learning to create and creating to learn9.

Wikipedia is an example of the confluence of these ‘connecting’ and ‘creating’ themes. The online encyclopedia allows anyone with digital device having internet connectivity to add to its repository. Several editors can edit the same page, across space and time.

We asked students to make two-member teams, with at least one member comfortable in English and the other, in Kannada. The former would try to understand and interpret the article on the English Wikipedia and that the latter would write the translated article on the Kannada Wikipedia. Either would have found this task impossible, together they could attempt it.

We taught students to use HAMT; they created the initial version of the English Wikipedia page in the Kannada Wikipedia, using the ‘auto-translate’ option available in the Wikipedia content translator10.

We also taught them to use the ‘voice to text’ feature, available on their digital devices11, where the team could read the SL, orally translate into text in the TL, which the software converted to text. This text was copy-pasted into the Kannada Wiki page.

The MediaWiki approach allows continuous refinement, instead of having to ‘get it perfect the first time’, making it easier to begin translation and then improve it gradually. This approach can expand the possibilities of involving teachers in translation on a large scale. ITfC’s Karnataka Open Educational Resources (KOER) project, which has both English and Kannada MediaWiki repositories12, adopted this approach. Teachers and ITfC members create content on either repository and translate the content into the other repository, at different points in time.

HAMT tools13 often capture our translations to refine what they hold, making machine translations more reliable over time14. Our regular use of the online translation tools can refine both the tools and their associated repositories. This is an example of ‘artificial intelligence’ (rather ‘machine learning’) that is unarguably beneficial to humanity. Though, its ownership should be public rather than private, for it to fully benefit society and not held ransom to the owners’ commercial interests.

As HAMT's accuracy increases, translation could become automated, however, HAMT will be more error-prone for complex articles, like many in the education domain. MAHT will continue to be relevant. Thus, while the use of digital tools and methods can certainly simplify the process of translation, translation skills are not fully replaceable by digital technologies.

8.Benefits

Conventional translation processes require immense expertise, which narrows down the number of people who translate. The digital methods discussed, can make trans-creation a much wider activity, enabling many more people to participate. We have encouraged around 250 student-teachers to translate English Wikipedia pages and publish it on Kannada Wikipedia. 300+ teachers have edited KOER content in English and Kannada.

This approach allows for tapping micro, complementing and incremental efforts across space and time. It allows for a combination of synchronous and asynchronous approaches to translation; people across locations can collaborate. Having more people with different perspectives can allow a richer exploration of ideas.

In addition, this approach also serves as a professional development activity. The APU translation project was a continuing professional development program for our translation team and gave us wonderful opportunities to deeply engage important texts in education. We use these translations in our work with Kannada medium government schools.

If teams of teachers, including those teaching languages, having diverse linguistic skills can be encouraged to come together to take on translation of articles relating to the education domain, this would act both to increase articles available in the target language and also support their continuing professional development. In this translations discussed, the SL was only English, similar approach would work for other SL’s as well, as most Indian teachers are multi-lingual.

9.References

- List of Wikipedias – Wikipedia

-

NCERT. National Curricular Framework, 2005 Position Paper on Teaching of Indian Languages.

-

Papert, Seymour. Situating Constructionism, 1991. Retrieved from http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html

-

Pushpak Bhattacharyya. Machine Translation, Language Divergence and Lexical Resources.

-

Sarukkai. Translation as Method: Implications for History of Science.

-

Shivaprakash H.S. Talk at webinar – retrieved from https://youtu.be/jNiENOc0jfU

-

World Englishes: Critical Concepts in Linguistics, Volume 4, edited by Kingsley Bolton, Braj B. Kachru.

10.Box on Translation

|

Translation – excerpt from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Translation Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. [1] The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between translating (a written text) and interpreting (oral or signed communication between users of different languages); under this distinction, translation can begin only after the appearance of writing within a language community. A translator always risks inadvertently introducing source-language words, grammar, or syntax into the target-language rendering. On the other hand, such ‘spill-overs’ have sometimes imported useful source-language calques and loanwords that have enriched target languages. Translators, including early translators of sacred texts, have helped shape the very languages into which they have translated. [2] Because of the laboriousness of the translation process, since the 1940s efforts have been made, with varying degrees of success, to automate translation or to mechanically aid the human translator. [3] More recently, the rise of the Internet has fostered a world-wide market for translation services and has facilitated ‘language localization’. [4] |

- 1. e.g. National Curricular Framework 2005 Position Paper on “Teaching of Indian Languages”

- 2. See http://www.ntm.org.in/languages/english/aboutus.aspx

- 3. Sarukkai. Translation as Method: Implications for History of Science.

- 4. Shivprakash H.S. in a webinar on ‘Thinking Translation, exploring Dialogues across Disciplines’- https://youtu.be/jNiENOc0jfU

- 5. Pushpak Bhattacharyya. Machine Translation, Language Divergence and Lexical Resources.

- 6. Alternative free and open cloud text-editors include Etherpad and OnlyOffice.

- 7. Wiki (MediaWiki) is a FOSS that supports collaborative editing. Wikipedia is the most popular MediaWiki repository, there are others like Wiktionary, Wikieducator

- 8. Vijaya Teachers College and Sri Sarvajna College of Education

- 9. See for instance, http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html

- 10. https://www.mediawiki.org/wiki/Content_translation

- 11. Voice to text feature available in Google doc

- 12. See https://karnatakaeducation.org.in/KOER/en/index.php and https://karnatakaeducation.org.in/KOER

- 13. For instance Google translate uses our translations to improve its translation engine

- 14. English-French and French-English machine translations are now regularly superior to human translations